THE ALAN VAUGHAN- RICHARDS HOUSE

- Words Jareh Das

- Photos Christina Nwabugo

Standing defiant against the city that has grown around it, one architect’s experimental Lagos home has become a quiet monument to the ideas and family he built it for.

Alan Vaughan-Richards first came to Lagos in 1956 as a fledgling associate with the Architects’ Co-Partnership, a firm of recently graduated students from the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London. He had already spent time working with the Iraqi Development Board and on projects for Oxford University, but it would be in Nigeria that he would make his mark. Over the next 30 years, he would come to play a key role in shaping the city’s urban fabric—first with Architects’ Co-Partnership and then, following Nigerian independence in 1960, leading his own practice and helping to develop a distinctly Nigerian form of modernist architecture.

Along with the masterplan and various buildings he designed for the University of Lagos, the house Vaughan-Richards built for his family in the affluent neighborhood of Ikoyi is considered one of his most notable projects. It originally consisted of just five circular interconnected spaces made from concrete: The first, Vaughan-Richards’ office, leads to the primary bedroom and then to the children’s room. The fourth area is divided in two—a narrow corridor with a bathroom that leads from the children’s room and a kitchen, both of which open onto the fifth space, a living room with a seating area cantilevered over a vast garden filled with fruit trees, plants and flowers. There are few straight lines anywhere in the house.

“The house really flows from one room to the next,” says Remi Vaughan-Richards, a filmmaker and the architect’s daughter, who still lives in the house. “But there was no privacy for us growing up—it was very much a home for a couple with young children.” Later, Vaughan-Richards added a second floor, accessed via a solid wood spiral staircase, with additional bedrooms and a study, each with large, louvered windows that shaded the rooms from the sun while enabling cross ventilation.

It’s just one of the many ways that the house responds to its environment, a key tenet of tropical modernism, which adapts the principles of modernist architecture to tropical climates. Vaughan-Richards had studied at the Architectural Association’s Department for Tropical Studies, which had been established in 1954 by leading modernists including Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew to promote the style. For them, West Africa had been a laboratory—a place to experiment with the use of louvers and brise-soleils to manage the heat and humidity—but they had neglected to engage with local architectural traditions. Fry even wrote that “there seemed to be no indigenous architecture” in the region; that it was up to Western architects to “invent an architecture which specifically met the needs of the West Africans.” The Vaughan-Richards house demonstrates that that was never the case.

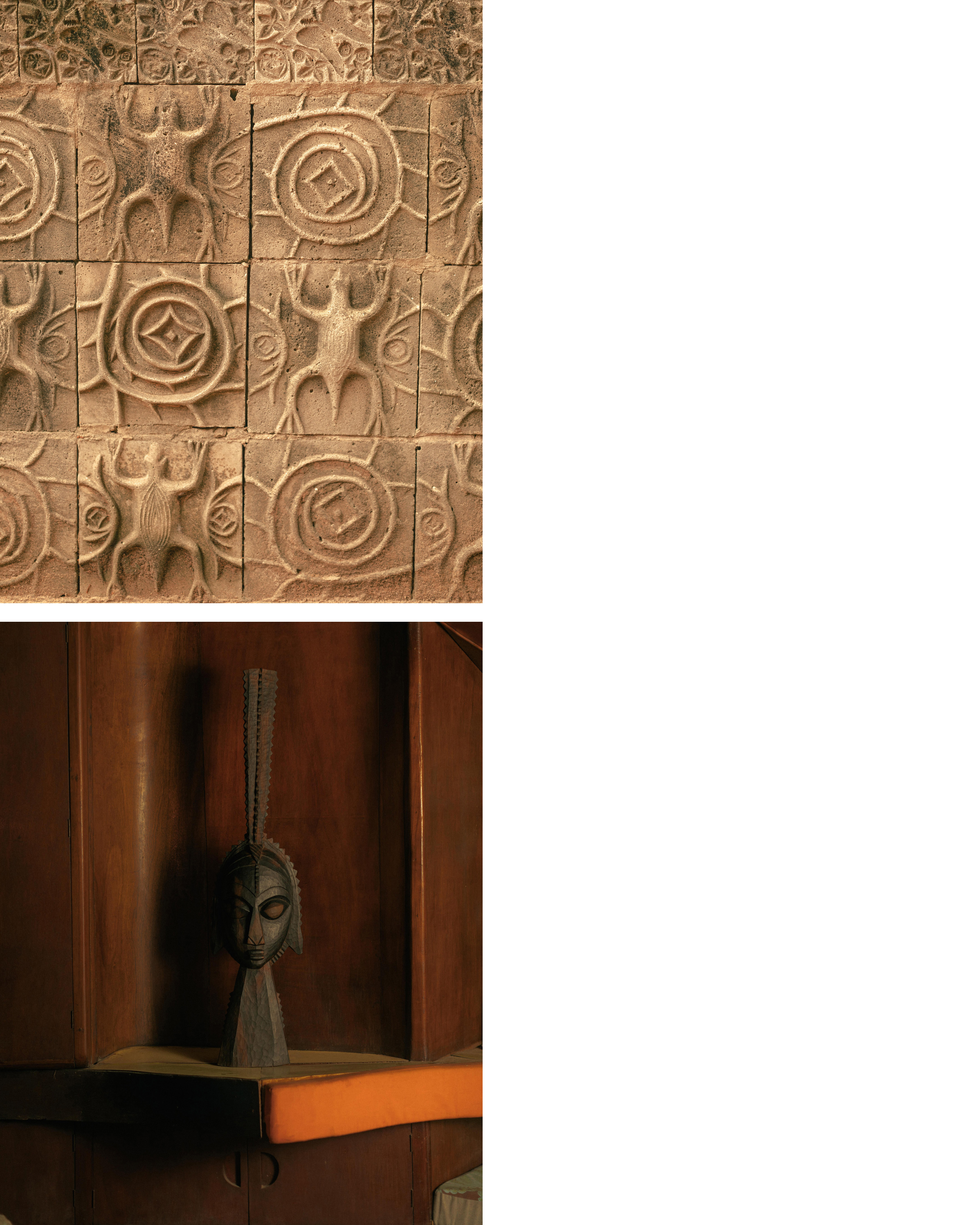

“Tropical modernism influenced my father’s ideas, but he challenged their design principles with this house,” says Remi. “He moved away from the rigidity of lines and geometry characteristic of the movement. Instead, he expressed himself by modifying the house as our family grew with it.” The techniques to shade the windows and encourage ventilation may have been drawn from tropical modernism, but other elements take inspiration from traditional Yoruba architecture, such as the ceilings of the circular rooms, which are made with palm fronds. Vaughan-Richards also collaborated with various artists and sculptors to produce the furniture, pillars, decorative panels and the carving on the front door, which depicts the house, surrounded, as it once was, by the lagoon, complete with fishermen and a forest with monkeys. The house is also filled with local Yoruba and Indigenous artwork; the masks, figures and earthenware pots curated by Vaughan-Richards and his wife, Ayo. “It is very much an experiment in mixing the two cultures,” Remi adds. “He was really ahead of his time.”

Thanks to Remi’s efforts to preserve her father’s legacy, the house remains a testament to that experimental and open-minded vision. Little has changed since Vaughan-Richards’ death in 1989, even if the city outside its unassuming concrete walls and gates adorned with motifs inspired by traditional Yoruba textiles is unrecognizable. “The area was once a sleepy fishing village, with a lagoon right in front of the house and accommodation for University of Lagos professors on our street,” says Remi, explaining that the lagoon has now been reclaimed and is being developed.

Still, there are plans to open the house further, and the geodesic dome in the garden was recently host to an exhibition of contemporary art, something Remi was motivated to do when she discovered her parents begun to hold exhibitions at the house shortly before her father’s death. With more exhibitions in the works, the house is set to have a new lease on life, albeit one that will be very much in keeping with its past.

“My father expressed himself by modifying the house as our family grew with it.”

Vaughan-Richards’ wife, Ayo Vaughan, was a descendant of one of the seven ruling houses of Lagos. Her respect and support for local and Indigenous artwork can be seen throughout the family home, from the Yoruba door panels to the ceramics and masks that decorate niches and alcoves.

Adjustable louvers are a hallmark of tropical modernist architecture, offering protection from sun and rain while allowing natural ventilation.