He wears a jacket by MAISON MARGIELA.

- Words Tara Joshi

- Photos Luke Lovell

- Styling Tana Grossberg

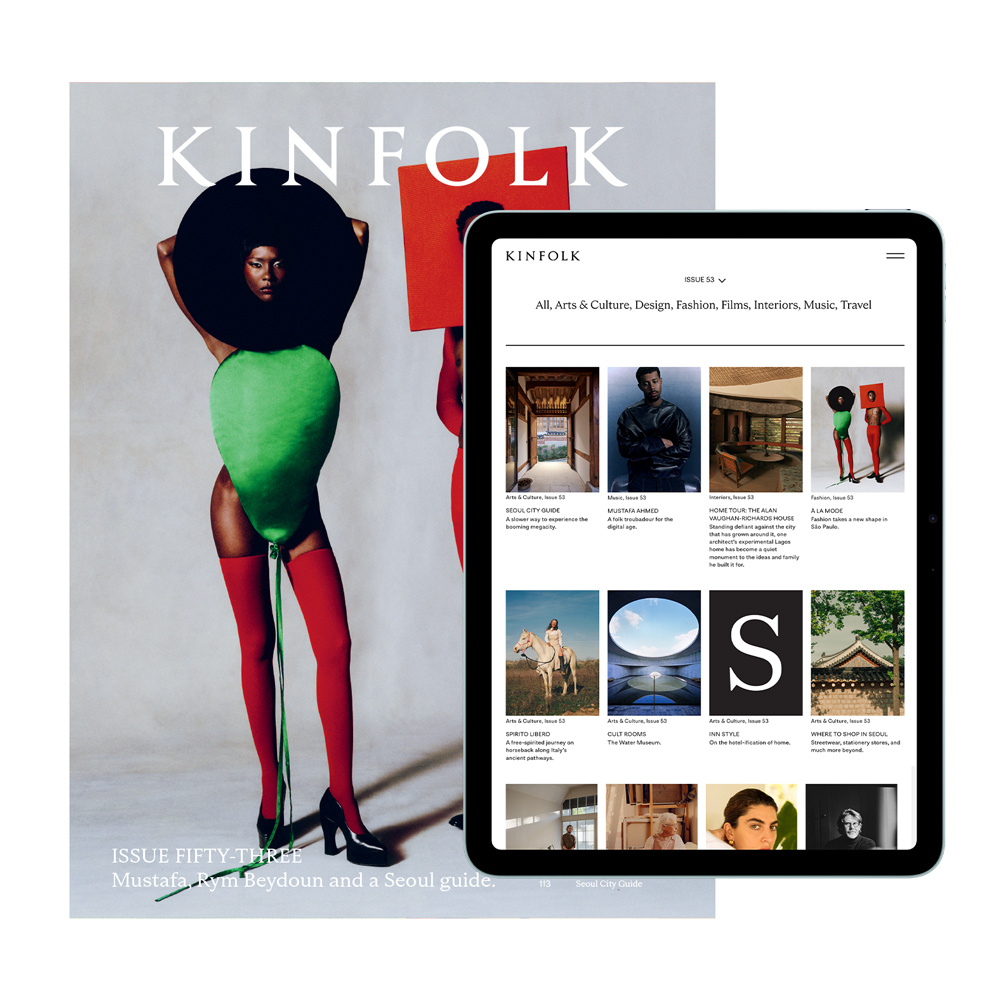

MUSTAFA

He wears a jacket by MAISON MARGIELA.

A folk troubadour for the digital age.

- Words Tara Joshi

- Photos Luke Lovell

- Styling Tana Grossberg

- Production Camp Productions

- Producer Alicia Zumback

- Production Designer James Lear

- Groomer Ghost (Jessica Pudelek)

- Studio Edge Studios

He wears a hat by NAMACHEKO and a tank top by MARNI.

( 1 ) Mustafa sampled Sudanese musician Abdel Gadir Salim on the track “Imaan” and has cited fellow Canadian folk musicians Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen as inspiring his songwriting.

( 2 ) Regent Park has undergone a $1 billion revitalization project over the last two decades. In May 2024, the last remaining buildings from the original 1940s urban plan were demolished.

Mustafa Ahmed is no stranger to tragedy. Since childhood, the Canadian-Sudanese artist has used his work—be it piercing adolescent spoken-word poetry or plaintive ’hood folk lullabies—to deal with the grief, poverty and systemic injustice he experienced coming of age in the shadow of conflict; whether it’s what his family left behind in Sudan, or what he witnessed growing up in Regent Park, one of the oldest housing projects in Toronto.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that in conversation the singer, songwriter and poet—formerly known as Mustafa the Poet, now going simply by Mustafa—seems far more enthusiastic when talking about the bigger picture than he is when talking about himself. As he says on a phone call in late May: “Community, to me, is the thing that keeps me alive.”

As a kid, Mustafa experienced the loss of neighbors and peers to both structural and direct violence; as he got older, he began to lose close friends. His debut EP, 2021’s arresting When Smoke Rises, memorializes them, creating space for his bereavements. Love and rage and mournful pleas are woven through the record, which melds elements of North American and Sudanese folk sounds.1 The EP was a success internationally, but little changed in Mustafa’s life in Toronto. In July 2023, his older brother, Mohamed, was murdered just streets away from their home. “They killed my brother in the very community I gave my life to,” Mustafa wrote on social media at the time, before going into a period of isolation.

“I have a very complicated relationship with my ’hood,” he says above the hubbub of the café he’s sitting in. These days, he’s mainly based in Los Angeles, though when we speak he’s in the UK, where he’s been working. He likes London, he says, because it’s like Toronto “without all of the weight.”

The need for distance from that weight is understandable after everything he has been through, but none of this means the 28-year-old is fully turning his back on where he comes from. “After my brother’s murder, I honestly decided that I was never going to return to the community,” he says. “I don’t think that I ever will. But even still, my responsibility as an artist from the beginning was always to do everything in my power to preserve what is being lost. This community is being gentrified, my friends and family are dying.”2

For all that this is deeply personal work, Mustafa is clear for the need to connect it to the wider world, rather than viewing his own losses in a vacuum. When he emerged from isolation following his brother’s death, Israel was in the full throes of its assault on Gaza following the October 7 attack by Hamas. “I think of the amount of people that are being lost around the world,” he says. “I’ve felt a lot of connection to the brothers and the mothers [in Gaza]. Those people are surviving being murdered in such a senseless and callous way, and so I feel a great privilege to be able to do what I do for the people that I lost.”

It’s not that his work is born out of a fear of him or his peers being forgotten, he clarifies. “I actually have no qualms with disappearing from every registry and from every memory. My grave fear is being misremembered.” He speaks about how, for too long, the wrong people have been tasked with defining the lives of young working-class Black men, with racist publications framing his late teenage friends as criminal adults and often erroneously connecting them with gang activity. “I cannot delegate any of that remembrance to anyone,” he concludes, “It has to be me.”

It’s still too painful for him to listen back to When Smoke Rises, though he recognizes the importance of continuing to perform these songs for an audience and eulogizing those he has lost. Mustafa’s long-awaited debut album, Dunya, makes sense as a next step. In collaborations with musicians including Rosalía, Clairo, Aaron Dessner, Nicolas Jaar and the comedian Ramy Youssef, the grief, rage and love of his previous work still lingers, and yet he is widening the lens. As he puts it: “If When Smoke Rises was about the moments after my friends passed, Dunya is about the moments before they did.”

Mustafa had been a difficult child. He recalls being disruptive in class and getting in trouble both in school and out of it. It was his sister who introduced him to poetry, in an attempt to connect with him. Though these days he feels fraudulent laying claim to being poet, it was the art form in which he first found a way to express himself creatively.

“Community is the thing that keeps me alive.”

Mustafa wears a shirt by JIL SANDER.

( 1 ) Mustafa sampled Sudanese musician Abdel Gadir Salim on the track “Imaan” and has cited fellow Canadian folk musicians Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen as inspiring his songwriting.

( 2 ) Regent Park has undergone a $1 billion revitalization project over the last two decades. In May 2024, the last remaining buildings from the original 1940s urban plan were demolished.

Mustafa wears a shirt, trousers and sandals by JACQUEMUS.

Mustafa wears a jacket, shirt and trousers by GUCCI.

( 3 ) After “A Single Rose” gained traction, The Toronto Star wrote a profile of Mustafa, noting how the 12-year-old’s poems about poverty in Africa and violence in Regent Park “make white adults cry.”

( 4 ) Members of the Youth Council help guide the Trudeau government on programs and policies that might benefit Canada’s young people, such as education, the economy and climate change.

( 5 ) Sudan has been in the grip of a civil war since April 2023—a direct result of a power struggle between two generals within the country’s military. Human Rights Watch has since expressed fears over ethnic cleansing in the country’s Darfur region, where 15,000 people from Masalit and non-Arab communities were killed in 2023.

( 6 ) “Haram” is an Arabic adjective that describes anything forbidden by Islamic law. Some Muslims believe musical instruments are haram and only vocals are allowed.

( 7 ) Morrison’s work at Random House can be viewed as a political project in that she helped to create a lasting record of the work of activists, marchers and protesters long after their activity had subsided. She edited the work of Black Power activists, including Muhammad Ali, Huey Newton and George Jackson, and was responsible for seminal works associated with the women’s movement, including the radical Lesbian Nation by Jill Johnston.

You can still find a video of a wide-eyed 12-year-old Mustafa reciting his poem “A Single Rose” on YouTube. In the incredibly earnest performance, he delivers lines like, “Can’t we spare some time and share a life line / and let people know that life doesn’t have to be a nightmare?” with precocious aplomb.3 The directness of his poetry laid the groundwork for the lyrics he started writing when he was 16, though he considers it to be different than writing poetry. “They’re individual skills which require their own time and attention,” he says. “Songwriting comes with its borders, it comes with having to surrender to the chord progression or melodic structure—there are words that don’t sing well; it’s difficult to write effective poetry. But it’s a form that can be boundless, there is no shortage of possibility in the way we can explore a poem; it is expression in its truest form.”

“There is no shortage of possibility in the way we can explore a poem; it is expression in its truest form.”

One day, he hopes to return to poetry, but his history with the medium is not without its uncomfortable memories. It was the kind of thing that could easily be co-opted—Mustafa as a lone, worthy poet amidst his other, more troubled peers. Indeed, in 2016, Mustafa became part of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Youth Council, a move which he has since disparaged (he told Pitchfork in 2020: “I was on his council when I was young, naive, and thought that I was gonna advocate from the inside. But no one gives a shit about you, fam, and no one gives a shit about me”).4 “I think we have to be diligent about who we are choosing to be in community with,” he says, reflecting on it now. “It’s one thing for us to have a clear sense of the communities that we are from, but sometimes I think we underestimate the ways in which that can be diluted or contradicted by who we choose to stand beside.”

Again, everything comes back to a sense of the collective for Mustafa. The past decade has seen “self-care” commodified as a hyper-individualistic pursuit, but it doesn’t seem unwarranted to wonder how Mustafa makes time to look after himself when his working and personal lives overlap so much, and when he deals with his trauma in such a public forum. But for Mustafa, care is a communal pursuit. “Growing up among Muslims and East Africans, there were those communal activities, gatherings and conversations, the sharing of food and feeling and beds and water; that was, in a lot of ways, what self-care felt like,” he says. “The best I feel in the face of some of the vitriol is being able to nurture the love I have around me. As long as that love exists it is proof of living, that life has not lost all its color. Self-care requires an exchange, it’s about giving.”

It’s a mindset that was evident in the benefit concert he organized for Gaza and Sudan in New York in early 2024, which featured performances by Clairo, Stormzy, Omar Apollo and Daniel Caesar.5 Mustafa himself has consistently used his art as a political medium—on Dunya, there is a track called “Gaza Is Calling” about his childhood friend living in the occupied territory (with lines like “Every time I say your name, there’s a war that’s in the way”).In the course of our call, we talk at length about the unraveling of democracy and the cognitive dissonance of university students being taught about colonialism and genocide and yet being reprimanded for the campus encampments that sprung up in 2024. Still, he recognizes that it can be scary for an individual to step up and speak out: “It was why it was important for me to do the concert, to get a lot of artists together, so that their hesitation dissipates when they see how many of their peers are joining them on the stage.”

To Mustafa, there is even something communal in his co-writing credits on songs by the likes of the Weeknd, Camila Cabello and Justin Bieber. “It has a kind of joy that I can’t find in writing my own songs,” he explains. “It’s the function of making myself small in someone else’s dream, you know? Being able to do everything in my power to help hold up a mirror to another artist is far less daunting than finding the tools to hold [a mirror] toward myself.”

He pauses. “And I think in a lot of ways, that is the optimal way of living this life…. Seeing yourself as a small part in a larger thing that is moving.”

In Islam, dunya refers to the temporal world, including all its flaws. “In Arabic, we often speak about struggling with the dunya,” Mustafa explains. “And I think that speaks to how lost one can be in it.”

On the album, Mustafa grapples with his faith after everything he’s lost, all while trying to understand whether he should even be writing his songs when he is aware that for some Muslims, making music is considered to be haram.6 There are certain corners of the internet where he is lambasted for conflating his faith with making music, and he is sympathetic to people’s concerns. He speaks about the beauty of Sufism—a mystic form of Islam—and its music; how, whether you have faith or not, listening to it can make you feel connected to some higher power. “Sufi music inspires me deeply, and it’s part of why I’m able to do what I do,” he says. “There’s a lot of different scholars that believe music [in Islam] can be permissible depending on what the message is, as long as the messaging is pure and not driving people away from the path of goodness and God.”

( 3 ) After “A Single Rose” gained traction, The Toronto Star wrote a profile of Mustafa, noting how the 12-year-old’s poems about poverty in Africa and violence in Regent Park “make white adults cry.”

( 4 ) Members of the Youth Council help guide the Trudeau government on programs and policies that might benefit Canada’s young people, such as education, the economy and climate change.

( 5 ) Sudan has been in the grip of a civil war since April 2023—a direct result of a power struggle between two generals within the country’s military. Human Rights Watch has since expressed fears over ethnic cleansing in the country’s Darfur region, where 15,000 people from Masalit and non-Arab communities were killed in 2023.

( 6 ) “Haram” is an Arabic adjective that describes anything forbidden by Islamic law. Some Muslims believe musical instruments are haram and only vocals are allowed.

( 7 ) Morrison’s work at Random House can be viewed as a political project in that she helped to create a lasting record of the work of activists, marchers and protesters long after their activity had subsided. She edited the work of Black Power activists, including Muhammad Ali, Huey Newton and George Jackson, and was responsible for seminal works associated with the women’s movement, including the radical Lesbian Nation by Jill Johnston.

Mustafa wears a jacket by ISSEY MIYAKE.

For Mustafa, Dunya is not only about examining his faith but about reflecting the nuances of the lives in his neighborhood. As he puts it, “the dunya is quick!” Rather than reducing people to their deaths, to the ugliness of fear and vengeance, he wants his work to focus on the fleeting beauty of it all. The warmth and intimacy he has shared with his loved ones are given new life and light with textures of oud, folk singing, bird song and spoken word. There’s one particularly harrowing moment on the song “Leaving Toronto,” where he sings over gentle guitar that, if he gets killed, people should make sure he’s buried next to his brother, and make sure that his killer has enough money for a lawyer. He wants to connect people and their struggles, to encourage solidarity and people coming together in community, but most of all, to make space to remember the truth of it all: to recognize the failure of systems rather than individual people. He nods to Toni Morrison, who, before writing her own novels, spent years of her life as an editor at Random House amplifying voices from the Black Power and women’s movements:7 “I think that that documentation is our responsibility. Like, to be a recording artist, our responsibility is to record a moment in time as it’s happening.”

Mustafa stresses the importance of music in this pursuit. “Sometimes you look at a photo, and you can’t remember what you were feeling when that image was taken,” he muses. “You know it was taken, you’re smiling, but sometimes you need someone to remind you what the emotional landscape was. For me, that is what song is for. Song is an emotional account in an infinite form. I need that sonic remembrance.”

“That is the optimal way of living this life…. Seeing yourself as a small part in a larger thing.”